Thursday, March 25, 2010

The history behind Easter traditions

Lent, Mardi Gras, Ash Wednesday and Maundy Thursday: these are all terms heard a great deal at this time of year. But what exactly do they mean and where do they come from? The special dates and traditions that are upheld as the days draw near to Easter Sunday have a long and intriguing history in Christian practice.

Most of the West’s time-honoured Easter traditions began in Europe, where Lent coincides with the beginning of spring. The words ‘Lent’ and ‘Easter’ are both derived from old English words: ‘Lent’ is an ancient Anglo-Saxon word that means ‘springtime’, and ‘Easter’ comes from the word Eastre or Eostre, which was the name given to the Goddess of Spring, who represented dawn and new light. As so frequently occurred, early church leaders adapted pagan traditions to fit in with the newly introduced Christianity. The already existing focus on the new light of the spring season thus came to refer to the spiritual dawn or new light Christ brought into people’s lives when he defeated death by rising from the grave.

Lent, which is forty days long, begins on Ash Wednesday, a day so named because in the Old Testament men and women covered themselves with ash during times of sorrow. The church adopted this practice during Lent as a sign for sorrow over one’s sins. Ash Wednesday thus heralds the start of a period in which men and women traditionally adopt a sombre and prayerful attitude, focusing on self-discipline, self-reflection and partial fasting (and also penance for Catholics). Lent then ends on Easter Sunday.

By the Middle Ages, food restrictions during Lent were a matter of enforcement; no meat, dairy or eggs were allowed, these being thought of as foods that give one pleasure. So the days and weeks leading up to Lent thus became a time when all the rich and fatty foodstuffs in one’s parlour were to be used up before Lenten fasting begins. These days became days of ‘carnival’, a word derived from the Latin for ‘a farewell to meat’. Shrove Tuesday – the time when Christians ‘shrive’ themselves, or confess their sins – is the last day of carnival, and it thus also became a day known to many as Fat Tuesday (or Mardi Gras in French).

In some areas Fat Tuesday it is also known as Pancake Tuesday. In the English town of Olney women have, for the past five hundred years, met in the town square with hot frying pans and raced one another to the church while flipping pancakes in the air.

In the first century, Lent was only forty hours long, Christians observing the actual period during which Jesus lay dead in the tomb. Lent was then broken at 3am on Easter morning with the church meeting to celebrate. I remember as a young girl in the Anglican Church how we would meet in the dark at 5:30am for an early Easter Sunday service. We would light candles and hold vigil for the ‘light’ of Easter Day. When first light came we would all wildly shake and rattle homemade instruments to celebrate Jesus’ rising from the dead.

The hot cross bun, also popular in the West, was supposedly first baked by an English monk who was moved to compassion when he saw poor, hungry families on the street during Lent. He baked the buns, added a symbolic white cross on the top, and gave it to them, hoping they would not be robbed of the joy of Easter.

The Sunday before Easter Sunday is Palm Sunday, when Jesus entered Jerusalem on a donkey and men and women waved palm fronds at him and also laid them on the ground so as to provide him with a softer path.

The last week of Lent is Holy Week. The first notable day during Holy Week is Maundy Thursday. It was on Maundy Thursday that Jesus sat around the dining table with his disciples and gave them the commandment to “love one another as I have loved you”. The Latin word mandatum, from which comes ‘Maundy’, means ‘commandment’.

The following day, Good Friday, Jesus was crucified. It is a “Good” Friday because he took on himself the punishment that mankind deserves, but it is also known as Black Friday in many parts of Europe because Christians remember the darkness and suffering Christ endured on their behalf.

The day for observing Easter is different every year because in the fourth century church leaders agreed that Easter Day would be every first Sunday after the full moon that follows the Spring Equinox (20 or 21 March).

In the Middle Ages, eggs were given to children and servants on Easter Day, a lovely gift because dairy foods had been denied everyone during Lent. The egg is also an obvious symbol of birth and life. It predates Jesus’ crucifixion as a sign of new life, but early Christians adapted its meaning so that the eggshell represents Christ’s tomb and the emergence of the bird represents his victorious breakout from the tomb. Today the symbolism of the egg remains, but the egg has been turned into a chocolate egg.

Easter Sunday is all about celebration, with Christians rejoicing over Jesus’ resurrection from death. Early Christians used to hold feasts, dance and sing, and play practical jokes on one another, celebrating the ‘final joke’ that Jesus played on the devil when he rose from the grave.

Labels:

Ash Wednesday,

Black Friday,

Easter,

Fat Tuesday,

Good Friday,

Lent,

Mardi Gras,

Maundy Thursday,

Shrove Tuesday

Wednesday, March 17, 2010

Sir Harry and Lady Smith

In this week’s blog I am going to tell you a love story. And if you read till the end you might be surprised to learn the relevance of the couple’s story to South Africa.

In this week’s blog I am going to tell you a love story. And if you read till the end you might be surprised to learn the relevance of the couple’s story to South Africa.The story takes place in the early 1800s between an English officer, Sir Henry George Wakelyn Smith, and a Spanish lady of equally long name, Juana María de los Dolores de León. They met and fell in love through unusual – even providential – circumstances.

Henry (or Harry as he was known) Smith was born in Whittlesey, Cambridgeshire, in 1787. In 1805 he joined the British Army. He was sent to fight in South America the following year as part of the British invasion of the Río de la Plata. In 1807 he was taken prisoner when the Spanish defeated his unit in Buenos Aires. He returned to England after only a few months of captivity but it was during this time that he learned to speak Spanish.

Harry met Juana María in 1812, when he was twenty-four. He was in Spain at the time, fighting with the 95th Rifles in the Peninsular War. The Peninsular War was part of the larger Napoleonic Wars, and as such British forces had been sent to the Iberian Peninsula in an effort to keep Napoleon from conquering and controlling all of Europe.

On 7 April 1812 British and Portuguese troops successfully stormed the Spanish town of Badajoz and thus brought to an end their besiegement of it. The victorious British soldiers, much to the horror of Smith and his fellow officers who were camped outside the city walls, were barbarous in their pillaging of the captured town. Smith later wrote of the event, saying:

“The atrocities committed by our soldiers on the poor innocent and defenceless inhabitants of the city, no words suffice to depict. […] too truly did our heretofore noble soldiers disgrace themselves, though the officers exerted themselves to the utmost to repress it, many who had escaped the enemy being wounded in their merciful attempts!”*

It was at this time that two Spanish sisters of noble birth^ approached the officers, seeking protection. The war had orphaned them, and they thus had nobody to defend them against the looters. They had blood trickling from their ears where soldiers had ripped off their earrings. The younger sister, Juana, was freshly out of the convent and only fourteen years old. Smith instantly stepped forward once they had made their appeal and he and Juana were married only a few days later.

Juana decided not to go to England to live with Harry’s family, but instead chose to remain with him, travelling with the luggage carts, sleeping in the open, and putting up with the hardships of a military life. She was the darling of the army, adored and admired for her beauty and courage. During one battle Juana was told Harry had been killed. She ran out onto the battlefield in a desperate search for him. She later learned that he had fortunately only been wounded.

Juana travelled all over the world with Harry, accompanying him on all his various postings (save for a short period in 1812 when he served in the British-American War). After a few years Juana converted to Anglicanism and was thus disowned by her remaining Catholic relatives.

In 1828 the couple moved to the Cape in South Africa where Harry worked hard to develop good relations with both the Xhosa and the Dutch. They were relocated to India in 1843, but were back in South Africa by 1847, where Harry – Sir Harry by now – was made Governor of the Cape Colony and High Commissioner.

Sir Harry and Lady Smith, as she became known, were well liked by many, and the result of this was that many towns in the countries where they served were named in their honour. Most notable of all the South African town names that can be attributed to them are: Ladysmith in KwaZulu-Natal, Ladismith in the Western Cape, and Harrismith in the Free State. Incidentally, Ladysmith in British Columbia was so named because 7,000 Canadians fought in the Anglo-Boer War and when Ladysmith, Natal was finally liberated from its besiegement, the Canadians’ patriotism towards Imperial Britain was high and the name Ladysmith was thus adopted for their Canadian town.

Sir Harry and Lady Smith are largely remembered today because of their great love story. Georgette Heyer’s popular novel, The Spanish Bride, was written based on their lives during the Napoleonic Wars. Their marriage, though childless, lasted for forty years, ending when Sir Harry died on 12 October 1860. Twelve years later, to the day, Lady Smith followed him.

______________________________________________

Footnotes:

* Harry Smith, Autobiography, from the University of Pennsylvania Digital Library Project. http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/hsmith/autobiography/harry.html.

^ Their great-grandfather was Juan Ponce de Léon, the first European to explore Florida while looking for the fabled Fountian of Youth.

Thursday, March 11, 2010

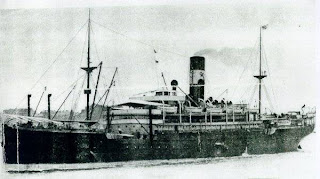

The disappearance of the SS Waratah

Last year I wrote a centenary article for a regional newspaper about the baffling disappearance of the SS Waratah. I still find it a gripping story and thought I would re-air the article for a geographically wider audience…

The SS Waratah, a British luxury steamer carrying 211 passengers and crew, set sail in 1909 from Durban to Cape Town and then disappeared somewhere off the east coast with all on board. Sometimes called the ‘South Atlantic Titanic’, the 465 ft ship has never since been found.

The Waratah was built in Glasgow for the British company Blue Anchor Line and was named after the emblem flower of New South Wales. It was to be the company’s flagship, serving as a passenger and cargo ship, taking European emigrants to Australia and then returning with freight.

The Waratah had a hundred first class cabins, eight state chambers, a salon and a lavish music chamber. On outgoing journeys the cargo holds could be converted into dormitories that were able to transport up to seven hundred steerage passengers. She was an immense ship, capable of carrying enough stores to survive at sea for a year, as well as having a desalination plant for producing drinking water. What she did not have was a radio, but at the time this was not uncommon.

In July of 1909, having already completed a successful maiden voyage, the Waratah was returning home from Melbourne, via the ports of Durban and Cape Town, on its second voyage. When it reached Durban, a few passengers disembarked, and one passenger, an engineer, cabled his wife in London, saying: “Booked Cape Town. Thought Waratah top-heavy, landed Durban. Claude.”

In a 17 December 1910 article in The Times Claude G. Sawyer claimed that he had had nightmares of pending disaster whilst en route to Durban and that he had been alarmed at the slow roll of the steamer, which did not quickly right itself after having been tilted by a swell. So although he was booked through to Cape Town, Sawyer decided to disembark in Durban and sent his wife the above cable. He relayed his nightmares to the manager of the Union Castle Line the morning after disembarking, and this action later helped save his reputation, as he had spoken of his fears before the Waratah’s disappearance.

The Waratah left Durban on 26 July and was due to arrive in Cape Town on 29 July. On the 27 July she passed the SS Clan McIntyre off Port St Johns and the two exchanged signals. This was the last verifiable sighting of the Waratah. Later that same day the weather worsened, creating strong winds and great swells.

The Union Castle Liner Guelph passed a ship during the storm and exchanged signals via lamp, but because of the poor visibility created by the storm, the crew could only make out the last three letters of the passing ship: “T-A-H”.

That same evening the Harlow saw a ship almost 20 km behind her, ploughing through the waves. The Harlow’s shipmate saw two bright flashes coming from the same direction, and then there was blackness. But he deduced that the flashes had been caused by brush fires on the shore, and he and the captain agreed that it wasn’t worth noting in the log. Only when they heard of the tragedy did they think that it was perhaps significant.

After the Waratah’s disappearance, there was a Board of Trade inquiry that focused on the supposed instability of the ship. Sawyer, in his interview with The Times, said that the entire journey to Durban had been uncomfortable, with the ship’s rolling reaching a 45 degree angle and more than one passenger being knocked off balance and injured.

But there were those who thought the ship stable; it had been given a “+100 A1” rating when tested for seaworthiness, and the Waratah’s design was heavily based on that of the Geelong, which had performed very successfully. And so the inquiry could discover nothing conclusive.

More than one rescue ship was sent to look for the missing Waratah. The HMS Hermes, searching in the area of the last sighting of the Waratah, encountered such strong, high waves that she strained her hull. The SS Wakefield, chartered by relatives of Waratah passengers, searched for three months, finding nothing.

Twenty years after the incident, Edward Joe Conquer, a Cape Mounted Rifles soldier, claimed to have seen a ship roll over and sink off the coast of the Transkei on the day of the Waratah’s last sighting. But many have questioned his integrity. And for his words to ring true of the Waratah, the ship would either have had to have turned around to return to Durban, or have lost engine power, as it was farther north than it logically should have been after passing the Clan McIntyre.

One of the most widely held theories of what occurred is that the Waratah was overwhelmed by a rogue wave that filled its holds and quickly sunk it. Either that, or the same wave overturned it, aided by the perhaps top-heavy nature of the ship. The latter option helps explain the lack of debris, as any persons or buoyant objects would have been trapped under the overturned deck. On leaving Durban, the Waratah had had in its holds 6,500 tons of food and lead concentrate. If a freak wave did hit it, the cargo could have been dislodged and as such would have helped to capsize the ship.

After the ship’s disappearance there were, however, two possible sightings of floating bodies near the Bashee River mouth, but neither were picked up – if they even were human corpses – and they cannot be linked to the Waratah with any certainty.

The freak wave theory gained greater prominence later in the century, redefined as the ‘hole’ phenomenon. In 1973 Professor Mallory, an oceanographer at the University of Cape Town, published a paper about the prevalence of abnormally large waves off the east coast of South Africa. He argued that the strong Agulhas current, along with the narrow continental shelf and a severe storm, could work together to create waves of up to 20 m in height, which would be large enough to swallow up a ship even as big as the Waratah.

Another theory is that there was an explosion in one of the coalbunkers, which would explain the supposed sighting of flames as witnessed from the Harlow. But such an explosion would not have sunk the whole ship without there being time to launch a lifeboat. (Unlike the Titanic, which sank three years later, there were enough lifeboats for all onboard.) And as with all the non-paranormal theories, it still doesn’t answer the question of where the wreckage is.

Other less accepted theories are that the ship was caught in a whirlpool or that an upsurge of methane sank it. In 1899 the Waikato had lost power and drifted for fourteen weeks before being recovered; many at the time speculated that the Waratah had lost power after being hit by a freak wave or having had some sort of mechanical breakdown, and that it was similarly adrift. This would explain the absence of a shipwreck. David Willers wrote a book arguing that the ship had drifted all the way to Tierra del Fuego.

The writer Clive Cussler worked in partnership with Dr Emlyn Brown, head of the South Africa National Underwater & Marine Agency (NUMA) and the foremost researcher into the disappearance of the Waratah, and the two men spent decades searching for the wreck. Since 1983 Brown led several expeditions to inspect the remains of ships hoped to be the Waratah.

In 1999 Brown announced that the wreckage of the Waratah, fitting the location described by Conquer, had finally been found. An underwater expedition was organised. But Brown had to later regretfully report that the wreck thought to be the Waratah was in fact a WWII cargo ship that had been sunk by a German U-boat in 1942. In 2004 Brown announced that he had given up the search, stating he had “exhausted all the options. I now have no idea where to look.”

One thing is clear: the name Waratah has proved to be an unlucky one. No less than four ships of the same name sank between 1848 and 1894. Yet all four of those losses have known causes. It is only the SS Waratah that remains elusive.

Labels:

Cape Town,

Claude Sawyer,

Clive Cussler,

disappearance,

Durban,

Emlyn Brown,

Geelong,

HMS Hermes,

SS Waratah

Thursday, March 4, 2010

The impact of The Pilgrim's Progress

No other English work (excepting the Bible) has been so widely read over such a long span of time as has been John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress. Up until the twentieth century it was a standard household book in English-speaking homes, a common sight on bookshelves alongside the Bible. Most adults today have heard of the famous allegory, but few have actually read it, and even fewer are aware of the worldwide impact that the book has had and continues to have in terms of culture, religion, literature and language.

But first let me briefly set the scene. In 1649 Charles I was beheaded and a predominantly Presbyterian Parliament, headed by Oliver Cromwell, was instituted. These Parliamentarian years, known as the Interregnum, ended in 1660 with the Restoration, when Charles II was brought back from the continent to reinstate the monarchy. Charles re-established Anglicanism as the state’s enforced religion.

Bunyan – a poorly educated Baptist minister – wrote The Pilgrim’s Progress in 1675 while imprisoned in a Bedford gaol, where he was kept for twelve years because he had been preaching without a licence. Puritans (also known as nonconformists) were largely reviled under the Restoration and suffered many persecutions, including not being lawfully allowed to meet and worship according to their own doctrines. Bunyan was actually offered freedom from prison provided he refrain from any further preaching. But he famously replied: “If you release me today, I will preach tomorrow.” And so he remained in a dank gaol cell, separated from his wife, his children and his ‘flock’, and it was during this time that his daytime dream came to him about a pilgrim called Christian.

The Pilgrim’s Progress is the world’s most famous allegory. (An allegory is a story where people, place and object names clearly point to their representative meanings.) The allegory of Bunyan’s book, the idea of which is taken from the Bible, is a simple one: a man called Christian becomes aware of a heavy burden on his back (his sins) and so, at Evangelist’s urging, flees from the City of Destruction where he was born towards the Wicket Gate, where he will find the straight and narrow path that will lead him to the Celestial City. He faces many obstacles, hardships and dangers throughout his journey, but along the way he also receives help from others and is kept company by Faithful and then Hopeful.

The first edition was published in 1678 and before the year was out there was a need for a second one. In 1684 Bunyan wrote The Pilgrim’s Progress Part II – this story follows the pilgrimage of Christian’s wife, Christiana, and their children – in response to Part I’s huge success. Within the first hundred years of its printing, Part I was printed in thirty-three editions and Part I and II together in fifty-nine.

The Pilgrim’s Progress travelled quickly after its publication, and it received an even more eager reception in Scotland, Ireland and the colonies than it did at home, as gauged by its sales and the manner in which it was discussed. It was printed in New England three years after its first publication in England, and unlike the crude materials used by English publishers, the New Englanders – for the most part nonconformists who a generation before had left England in order to find a better way of life – thought it worthy of the most elegant binding. For them, Christian’s allegorical journey hit home in a big way, speaking as it did of a hard, dangerous journey, much like the one that they had literally experienced in sailing to New England and settling in its harsh climate. Six years after its first publication Bunyan wrote of Part I:

’Tis in New England under such advance,

Receives there so much loving countenance,

As to be trimm’d, new cloth’d, and deck’d with gems

That it may show its features and its limbs,

Yet more; so comely doth my Pilgrim walk,

That of him thousands do sing and talk.

Its translations came quickly. The Dutch and French had it by 1682 and the Germans by 1694. The Pilgrim’s Progress travelled across Europe with the persecuted as they fled to safer and Protestant parts of the continent. It also went with them to the Caribbean. The whole book (Parts I and II combined) later underwent even greater dispersion abroad as the result of missionary societies, arriving in India in the late 1700s and spreading all over Africa the following century. It was considered such an invaluable evangelistic tool that in 1847 a London Missionary Society ship heading for Tahiti carried not only 5,000 Tahitian Bibles but also 4,000 Tahitian copies of The Pilgrim’s Progress.

Today the number of translations is formidable, the figure being around two hundred. There are eighty African language translations alone. And let us not forget that there are also modern ‘translations’ for those who struggle with the archaic English of the original text.

The Pilgrim’s Progress was and still is popular with children. “This is the great merit of the book,” said Dr. Johnson, “that the most cultivated man cannot find anything to praise more highly, and the child knows nothing more amusing.”* For a child, the read is all about foul fire-breathing fiends and sword fights to the death, and about good men trapped in dark dungeons by cudgel-carrying giants who have seizures at critical moments. Victorian parents in particular were known to give it to their children to read in the hopes that the book would help in the task of teaching them religious and moral values, as well as make such things easier to talk about.

The general attitude towards Bunyan and his Pilgrim’s Progress has changed dramatically with time. In his own lifetime the book was the cherished possession of nonconformists. It did, however, gradually but thoroughly become adopted by all Protestants, regardless of denomination, and it became, as we have seen, a favourite of missionaries. So it is no longer the celebrated spokesman for a maligned few, but has rather come to be considered the property of all Protestants, including the established Church of England that once colluded in Bunyan’s imprisonment for propagating Puritan beliefs.

The Pilgrim’s Progress was initially ridiculed by the literati, who had no time for the writings of a tinker’s son. In England, “all the numerous [earlier] editions of The Pilgrim's Progress were evidently meant for the cottage and the servants’ hall. The paper, the printing, the plates were of the meanest description. […] The Pilgrim’s Progress is perhaps the only book about which, after the lapse of a hundred years, the educated minority has come over to the opinion of the common people.”^ And with the genesis of English literary studies in the late nineteenth century, scholars began to hail Bunyan as a genius, pointing to his natural talent for employing fluent and vibrant language.

Bunyan has also been recognised as a literary innovator. For his text to be didactic (Puritans loved to be edified and eschewed anything frivolous), his readers needed to be able to relate to the pilgrims’ journey. He caused his pilgrims to come alive in a manner foreign to the well-established genres of the epic and allegory, where characters were flat and heroic, lacking in human frailty and thus hard to connect with on any emotional level. Bunyan gave Christian, Hopeful and Faithful three-dimensionality or inner depth that foreshadowed the manner in which the novelists of the eighteenth century would paint their fictional characters. The pilgrims are allegorical but they are unique people as well, with specific personality traits, such as Christian being wise but not particularly tactful, and Faithful proving himself courageous but struggling with sexual temptation.

The Pilgrim’s Progress has not only entered into people’s homes throughout the centuries, but it also eventually became part of British and American popular imagination and public discourse. The numerous references to The Pilgrim’s Progress in subsequent novels, plays, poems, speeches, art and music bears testimony to the mark it has made on society. Thackeray’s novel, Vanity Fair (serialised in 1847-8 and dramatised in 1917), John Buchan’s novel, Mr Standfast (1919), and C.S. Lewis’s allegory, The Pilgrim’s Regress (1933), all made explicit use of Bunyan’s book for their titles. The influence of The Pilgrim’s Progress is especially noticeable in nineteenth-century literature, with Dickens, Charlotte Bronte, Mark Twain and Loiusa May Alcott as just four examples of prominent authors, besides Thackeray, who made reference in their novels to Christian and his pilgrimage. There existed such common knowledge of the allegory that writers could think and comment and describe in terms of The Pilgrim’s Progress, knowing their audience would pick up on and understand the references.

The Pilgrim’s Progress has also added to the English language, with original phrases such as Slough of Despond, Vanity Fair and Land of Beulah entering into some dictionaries. Other inventive names such as Hill Difficulty, Valley of Humiliation, By-ends, Mr Facing-both-ways, Little-faith, the Delectable Mountains, Giant Despair and Doubting Castle are also proverbial, having become part of common parlance and thus recognisable even by those who have never read the book. The dissenting beliefs of the Puritan minority have generally been remembered and written about unfavourably since their time, but Bunyan’s imaginative and succinct manner of expressing intangible concepts has led to the universal and lasting acceptance of much of his language and expression.

________________________________________________

For more on this topic or for detailed references, take a look at my thesis at www.meganabigail.com.

Footnotes:

* http://www.bartleby.com/217/0706.html

^ Macaulay, The Miscellaneous Writings and Speeches of Lord Macaulay (Encyclopediae Britannica, Poems, etc): John Bunyan (May 1854).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)